Happy New Year and welcome to 2012! With the holiday season quickly slipping from our grasp, it’s time to look towards our plans for ourselves and our quality of life. Maybe you’ve made a New Year’s Resolution to come to the gym more often, or go for a walk every day, or choose healthier meals more often. If you have – good on you! Goals are useful tools to focus your efforts. But is there a possible downside to this wave of new-year motivation you might be currently riding? Read on…

Motivation is a hot topic at any gym, and Inspire Fitness is no exception. Many of our clients are busy people, with many commitments and responsibilities, and ultimately a lot of pressures on their time. I’ve had more than a few conversations with Inspire Fitness members about the challenges of “staying motivated” despite being time poor, or feeling low on energy, or just plain disinterested.

Motivation is a hot topic at any gym, and Inspire Fitness is no exception. Many of our clients are busy people, with many commitments and responsibilities, and ultimately a lot of pressures on their time. I’ve had more than a few conversations with Inspire Fitness members about the challenges of “staying motivated” despite being time poor, or feeling low on energy, or just plain disinterested.

The concept of motivation is both alluring and head-scratching. You only need to look to the variety of advice blogs all over the internet to see evidence of this; from organisational management, to personal productivity, to budgeting and finances, the creative domain, and those who want to become and remain physically active, everyone wants to know how to get motivated and stay motivated. Interestingly, we only ever seem to talk about motivation in relation to things we don’t like doing. Ever hear of someone needing to “find the motivation” to sleep in, or eat their favourite food, or take a day off work?

Why do we think that motivation is so important? Certainly, the history of motivation as a concept is long and storied. Classical science contends that “…motivation is a primary cause of behaviour” (Gollwitzer & Oettingen 2001). You might think, “Perfect! Generations of scientists can’t be wrong, right? So if I want to keep up a regular exercise regimen, I just need to be motivated.” Simple. And yet, modern psychologists continue to debate the importance, meaning, and role of motivation in changing and sustaining human behaviour.

Though I am a researcher and a corrective exercise practitioner, I am not a psychologist. But even I have long-held reservations about whether we might be putting too many of our eggs in the motivation basket. From my experiences, there are four major problems with the idea of motivation with respect to establishing and maintaining regular exercise habits.

1. Motivation is volatile.

Anyone who has started an exercise program, then fallen off the wagon only a few weeks later can attest to this (*raises hand*). Motivation is highly volatile – it comes and goes, and it is prone to drop when you start to listen to your own excuses (“It’s too hot/cold/rainy to go to the gym”, “I need new shoes before I start back up with my morning walks”, etc.).

Anyone who has started an exercise program, then fallen off the wagon only a few weeks later can attest to this (*raises hand*). Motivation is highly volatile – it comes and goes, and it is prone to drop when you start to listen to your own excuses (“It’s too hot/cold/rainy to go to the gym”, “I need new shoes before I start back up with my morning walks”, etc.).

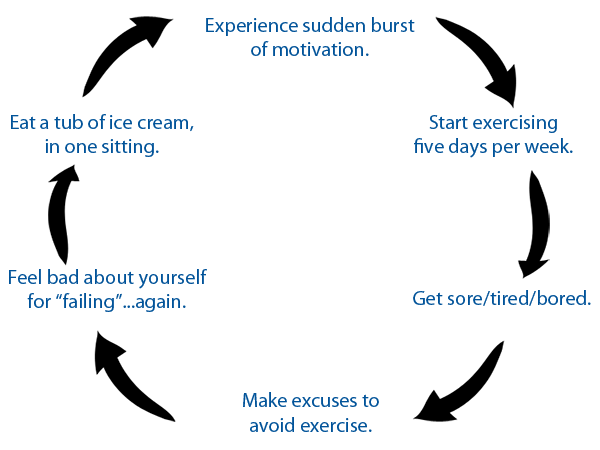

Drawing from my own struggles with motivation, to those I’ve observed in others, it seems that motivation has the life cycle of a sparkler. You strike a match, and with it comes an initial burst of energy, heat, and light. (You spot yourself in the mirror looking a little “out of shape”, and pledge to run 5 km every morning before work.) For a short time, this energy persists, sparks flying in every direction. (You stick firmly to your pledge. For two weeks.) After a while, though, the sparkle diminishes, and the burn out starts to become visible. (Things get busy at work, you come down with a head cold, and other things become more important or urgent. You decide to cut back your morning runs to Mondays only.) A short time later, the sparkler fizzles out lamely, and all you’re left with is a blackened stick. (Ruffled up by all your commitments, you’re tired and maybe even a bit bored with running. And after all, running once per week is not a huge improvement on not running at all, right? Might as well stop now.) No more bursts of light, no forward momentum. Not very impressive, is it?

At the beginning of an exercise program, having the motivation to show up and sweat it out is exciting. But it is often unsustainable.

2. Motivation depends on other factors.

For many, motivation comes in response to some sort of trigger: a traumatic event, a disconcerting feeling about your appearance or your health, a suggestion from a friend with (usually) good intentions. In such cases, motivation is reactive.

Here’s the thing: feelings are fleeting and often pass. Many events of the recent past become distant memories, in time. Suggestions are sometimes heard, but quickly forgotten. Or alternatively, the suggestions reach a level of oversaturation: too many suggestions provided too often, so nothing sticks.

The problem with motivation as a reaction response is:

a) Your motivation wanes when the trigger (the event, the feeling, the suggestion) ceases to be. I bet we all have that one family member that visits periodically, and always comments on how we could do without dessert every once in a while! This “friendly” suggestion may very well motivate us to take short-term action. But once that family member goes home, the trigger ceases to be. And with it goes our motivation for exercise and true change.

b) The lifespan of a motivation reaction is usually short. It ends when the trigger has been addressed, however superficial the reaction may be. It’s a story that is familiar to many, myself included. Step 1 – Watch a news story about Australia’s crisis of physical inactivity; Step 2 – Decide to go for a walk immediately; Step 3 – Get home from the walk, feel satisfied, avoid exercise for months afterwards.

3. Motivation is deceptive.

Tell me if you’ve heard this one (or said it yourself): “I’m really motivated to get fit this year. But first, I need to buy new runners, sign up for a fitness boot camp, tell all my friends about my new fitness crusade, download the latest GPS-tracking iPhone app for runners, research the best home gym systems, blah blah blah…”

This is not motivation. This is being enamoured with the idea of fitness. This is excitement about playing with new toys. This is hoping others will be impressed by how committed you are to your fitness. It’s a harsh assessment, but motivation can be a wolf in sheep’s clothing if you let it be.

4. Relying on motivation is ultimately self-defeating.

Everyone fails sometimes. In fact, there’s a strong case for failure being a good thing. The trouble with relying on your motivation levels to make your exercise habits stick is that failure kills motivation. After missing one session of your regular five per week, it’s easy to get stuck in a rut of self-blame, which only de-values all the effort you’ve put in up to that point in time. In your self-appointed shame, one missed session quickly becomes two, each failure feeding the next. But it doesn’t have to be this way. If motivation is not the driving force of your exercise habits, then failures become opportunities to clean the slate, dust yourself off, and try again.

Everyone fails sometimes. In fact, there’s a strong case for failure being a good thing. The trouble with relying on your motivation levels to make your exercise habits stick is that failure kills motivation. After missing one session of your regular five per week, it’s easy to get stuck in a rut of self-blame, which only de-values all the effort you’ve put in up to that point in time. In your self-appointed shame, one missed session quickly becomes two, each failure feeding the next. But it doesn’t have to be this way. If motivation is not the driving force of your exercise habits, then failures become opportunities to clean the slate, dust yourself off, and try again.

If motivation isn’t the answer, then what IS the answer?

It should be of no surprise to anyone that maintaining our good health through regular physical activity and mindful dietary choices is a lifelong pursuit. I’d forgive you for thinking that, for me, motivation is enemy number one. The truth is, harnessing the upswings of motivation can jumpstart you and your enthusiasm for exercise in this (hopefully) long and challenging adventure we call living! But I’d argue that motivation is not something to hang your metaphorical exercise hat on. There’s something else, far more stable and often more powerful in the long run, that can help to drive every aspect of your healthy living behaviours.

In short, my experiences and observations have added up to this:

Motivation can be useful, but commitment to a purpose is far better.

Got a question, comment, or query? Leave a comment below this blog post, and let us know your thoughts about the relationship between regular exercise habits and motivation.

Part two of this blog post series will explore the value of purpose and commitment for establishing regular exercise habits, and strategies to keep you going for the long haul.